How do you take the plunge and structure Agile innovation?

Agility and innovation, from myth to reality (3/3)

This series of articles aims to shed light on the obvious yet complex link between Agility and innovation, and to suggest ways to structure it. Once you have thought about it, it is time to put it into practice: 4 key ways of integrating the innovation approach into an Agile operating mode.

This article is the last in our “Agility and innovation, from myth to reality” trilogy. After highlighting the value of innovation in an Agile approach and beaten related prejudices, this final chapter deals with the concrete application in your daily Agile life.

PART 0 : Structuring the continuous innovation process

The continuous approach of innovation must be part of an overall strategic approach to the company, and linked to its development challenges. A huge program, therefore, which cannot be summed up in a few scattered actions. Still in the spirit of Agile, why not implement innovation in the image of the working method, via a Zero Sprint. The Zero Sprint is a methodological structuring phase upstream of the project. Very often rushed, or even omitted, it is nevertheless an essential investment for an efficient start. Ideally, the Zero Sprint of innovation is carried out at the same time as the project, but it can also be carried out afterwards, when the company or project team is ready to embark on the process.

This is the ideal place to carry out an initial diagnosis of the organization’s cultural and structural maturity to define its ambitions and the associated resources: what resources should be allocated? What governance should be put in place (distilled down to the teams or centralized)? What impact will it have on other functionalities and on product architecture? How to set up a feedback loop?

This involves asking all the questions needed to create the cultural and structural foundation for innovation within the organization. This foundation will form a working framework, with its own operating rules, which can evolve as the team matures.

PART 1: Creating and feeding an innovation backlog

There are inherent fears in any organization wishing to embark on an innovation process: the fear of the blank sheet of paper on the one hand, and the fear of fantasy on the other. Will teams have the creativity come up with truly innovative ideas? Will they come up with ideas in line with the company’s (or project’s) needs and challenges? In a nutshell, how to find the right balance between stimulating creativity and framing it so it is correctly targeted?

In parallel with its “product backlog” counterpart, it is important for the organization to have the means to maintain an “innovation backlog”. Initiated during the Innovation Zero Sprint, this can be fed not only by management, who can cascade topics with strategic stakes (“top-down” approach), but also by teams, who can escalate ideas. It is even interesting to use these two complementary channels.

Depending on the maturity of the team, it will be more or less necessary to devote time for ideation. The higher the level of innovation culture, the more the innovation backlog will feed on itself. On the contrary, a team with a low innovation culture will need support to propose and energize ideation. The frequency and regularity of sessions will vary according to the team’s ambitions and cultural evolution. Gradually, the team will acquire reflexes to identify in real time the subjects to be explored. In the long term, the difficulty does not lie so much in generating ideas but in capturing and transforming them.

It is key to apply different prioritization criteria from the classic backlog. At this stage, the objective is to explore. It is therefore not essential to have demonstrated the value of an idea in order to have the right to launch it. A simple framing exercise (based on a Lean Canvas, for example) is enough to give teams the opportunity to explore and experiment (with the help of a Minimum Viable Product – MVP), with the aim of demonstrating the value-added and/or economic viability – or not – of the idea. Let’s not forget, as we saw in article 2, that it is normal and even recommended for some ideas not to be reintegrated into the product backlog. Indeed, the success of an innovation approach does not lie in its ability to develop the full range of ideas but rather to provide a space of exploration and a decision-making capacity to target the most promising ideas.

PART 2: The IP Sprint, a sanctuary for innovation

In our first article, we explain that the only Agile method that explicitly addresses the notion innovation is SAFe ©, which proposes a temporal structuring in Program Increments. These PIs are made up of four development iterations and end with a particular iteration Sprint Innovation & Planning (IP). In other words, SAFe© invites us to make innovation a recurring sanctuary during the IP Sprint, so that even teams caught up in the continuous flow of development Sprints can have the opportunity to dedicate themselves to it. As we mentioned earlier, it is perfectly possible to apply this rhythm to all teams, whatever their size or the Agile method used.

Observations in the field nevertheless show that, in most cases, teams do not exploit this time to innovate. Situated at the end of the IP, this final iteration turns into the final stretch before the finish line, a relentless “sprint” to reach the targets. objectives. In other words, a buffer period to finalize the last deliverables of the iteration.

So is it time to pause activities during the IP Sprint? Should you stop production altogether to focus exclusively on improvement, innovation and learning?

There are many advantages: totally focused on these activities, teams are no longer distracted by other information that interferes with their concentration. This gives them the time they need to dive deeper into the selected themes. The IP Sprint creates a breath of fresh air, a break in the daily routine that helps employees to keep the motivation and commitment.

However, this is easier said than done. Such an outlook is likely to provoke an outcry from managers who see only a total halt to production. In fact, we will need to think about how to manage interdependencies and manage deliverables “deemed urgent”. Consequently, the corporate culture must be conducive to Innovation & Planning sprint protection.

Depending on ambition and investment it wishes to devote to innovation, the company or project team could review the methodology and adapt the duration of the IP Sprint: it is entirely possible to restrict the IP to a shorter duration than production iterations, in order to control the impact on deliverables. Indeed, while for some teams two weeks of IP (the duration recommended by SAFe ©) will seem too restrictive to innovate, others will see it as too constraining in the context of tight deadlines.

Another option is to continue production activities in parallel with those on IP themes. The choice of continuity makes it easier for managers to get on board, by maintaining a dynamic around essential day-to-day activities, while securing significant availability to devote themselves to innovation. It also has the advantage of mitigating any effort to “reconnect” with production topics, at the end of a rich and exclusive IP Sprint.

But the downside is considerable: without a real protection, will employees dare to take this break? What will be the participation rate if the workload and emergencies/unforeseen events continue? What results can the company expect to achieve with less time devoted to innovation? Without these breathing spaces, will the teams’ rhythm be sustainable in the long term?

PART 3: An IP sprint tailored to each organization

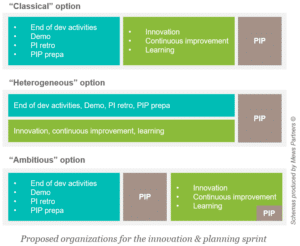

Whether the company opts to pause the activities or to continue production, it will need to structure the Sprint IP in such a way as to achieve the objectives it has set itself. As long as you are willing to take a step back from the SAFe © precepts, and depending on the maturity of your employees, several schemes are possible:

– Classic: divide the iteration into 3 main phases: PI closure (end development activities, Demo PI, Retro PI), Innovation (continuous improvement, learning and discovery, innovation, PIP preparation), & Planning (PI Planning).

– The heterogeneous: dividing the days between PI closing activities in the morning, and Innovation & Planning activities in the afternoon, before finishing with a more traditional PI Planning phase. Non-divisive, this planning allows for a daily compromise between development and innovation.

– The ambitious: invert the paradigms by interposing PI Planning (PIP) between the closing of the PI and the IP activities; this approach prevents the IP part from being absorbed by remaining development activities or by the preparation of the PIP, by deliberately placing it at the start of the next PI. By means of a systematic demonstration of innovation results at the end of the IP phase, a decision-making committee judges the maturity of subjects for integration into the Product Backlog; in case of positive arbitration, the teams concerned must proceed with a marginal adaptation of the scope and objectives of the PI to come.

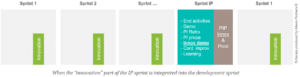

Our fourth, more impudent option consists of literally taking innovation out of the IP Sprint and planning regular work (the frequency of which is to be defined) during production sprints. This eliminates the risk of IP subjects being absorbed by the multitude of activities to be carried out in parallel, and emphasizes the desire to include innovation and production in a single cycle. As part of this structuring, teams considerably reduce the duration of IP sprints, shifting the load throughout the project. Of course, this means deducting this time from the availability of collaborators when calculating PI Planning capacity. This brings us back to importance of the notion of time sanctuary, and of establishing a protective mindset, so that the team grants itself the right to work on these subjects despite production imperatives. The frequency and regularity of slots will evolve according to the team’s maturity and ability to secure time for innovation activities.

This option enables innovation topics to be addressed in a continuous manner, without any mental or technical gaps. The IP sprint then becomes an iteration of analysis, during which the results of a period are assessed (development and innovation results exposure). This is a time of collective and personal enrichment (through continuous improvement, learning, etc.) and preparation for the new period ahead (prioritization, planning).

From innovation to production, there must only be a single step

While setting up an innovation is not the same as climbing Mont Blanc, it is nevertheless a sporting hike accessible to anyone who takes the time and knows how to prepare for it.

Contrary to common belief, innovation in Agile does not impose itself, it even requires advance structuring adapted to the company’s ambitions. During a Zero Sprint, we will lay the foundations for a continuous innovation approach and initiate an innovation backlog in line with the company’s vision and objectives. Considering the various solutions proposed in this article, each company (or project team) will then be able to determine the approach best suited to its aspirations and set up an innovation framework that is conducive to success.

Whatever the chosen structure, and depending on the team’s maturity, particular attention should be paid to setting aside time innovation, to support the cultural change initiated. This is a major challenge, which can be achieved by demystifying fears and legitimising the approach.

The ultimate challenge of any continuous innovation process lies in its natural transposition into the production backlog. The former must inevitably feed into the latter to establish its credibility and justify its relevance. With time, practice and appropriate support, this link will become increasingly obvious, fluid and fully integrated into the company’s habits and customs.

The serie “Agility and innovation, from myth to reality”